Do the math! More fertiliser, more profit!

2024. May 3., Friday

2024. May 3., Friday

Demand for food has increased significantly over the last few decades and this trend is expected to continue. Given the limited availability of arable land, the growing demand can only be met by intensifying production.

This will require, in particular, the use of varieties/hybrids with higher yield potential, irrigation farming, more rational and harmonious fertilisation adapted to the needs of intensive hybrids/varieties, more modern and productive agrotechnology (cutting-edge machinery and modern plant protection, etc.), while maintaining and improving soil fertility (e.g. achieving a positive NPK-balance) and meeting the requirements of environmental protection. Otherwise, we will not be able to exploit the genetic potential of the biological base, i.e. even if we buy the more expensive, higher yielding variety, we will not achieve the desired average crop yield.

Intensive farming not only means higher costs, but also higher yields; in case of intensive farming, the agrotechnical elements (variety selection, sowing, fertilisation, irrigation, crop protection) have a greater influence on average crop yield, while the ecological conditions (which are only partially or not at all under our control) have a lesser influence than in extensive farming. Let’s keep in mind that the nutrient content of the soil determines the yield as much as the amount of nutrients applied in that year. Since the availability of organic fertilisers in our country is limited (in principle, 1 t for each hectare of arable land, which is equal to 10–15 kg/ha of NPK per year), applying fertilisers is almost the only cost effective way of nutrient replenishment.

The events of 2022 and 2023 have led to significant increases not only in the prices of input materials, but also in crop prices.

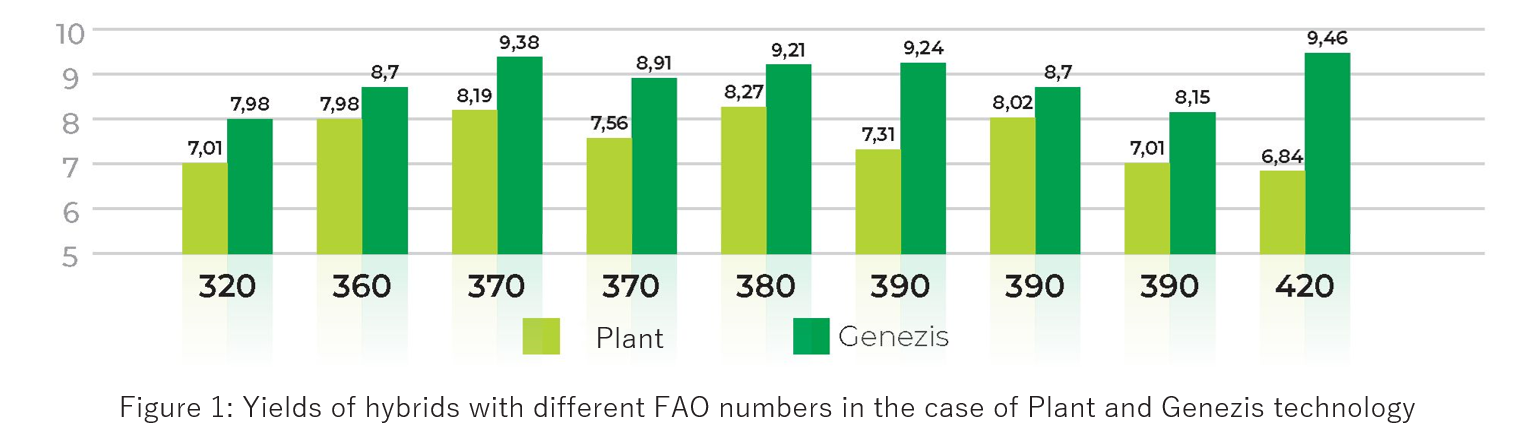

We have thousands of results from experiments in the last 15 years, some of which are presented here, together with profitability calculations of course, to illustrate that intensive farming (while also meeting the requirements of environmental protection) does pay off and can even be more economical and result in higher incomes. In addition, achieving average crop yields that are almost the same every year (or at least above a certain level) (i.e. yield stability) seems to have gained importance recently, as it makes the following year's production much more predictable, and the distribution of income more reasonable, serving the aims of farming and its development. In one of our variety trials, we tested nine maize hybrids with FAO numbers between 360 and 420. In the area (Szentmártonkáta), all hybrids were grown applying two different NPK-doses (Plant and Genezis), side by side in the same field.

In the case of the Plant technology, neither phosphorus nor potassium was applied at 150 kg of nitrogen active ingredient, because it was considered not justified for soils with higher than medium PK nutrient content. In the Genezis technology we recommended, 150/20/36 kg of NPK active ingredient was applied based on the principle that even with better than medium PK content of the soil, maize will respond well even to low doses of fresh PK fertilisation.

Taking into account the current prices, we calculated at a production cost of HUF 390,000/ha for the Plant technology and HUF 420,000/ha for the Genezis technology. We measured an average crop yield of 6.84–8.24 t/ha in the Plant field and 7.98–9.46 t/ha in the Genezis field, depending on the specific hybrid. At a farmgate price of HUF 75,000/t, depending on the hybrid, this represented an additional sales revenue of HUF 51,000–196,500/ha, HUF 21,000–166,500/ha additional income in favour of the Genezis technology. At a farmgate price of HUF 100,000/t, these were HUF 68,000-262,000/ha and HUF 38,000–232,000/ha respectively. It means that even on a soil with a better than average PK-content, it is worth to apply even a low dose of PK fertiliser, as it leads to higher yield and, more importantly, additional income. Moreover, the break-even point (the crop price at which total revenues equal total production costs, meaning there is no gain or loss) was by HUF 3,000–5,000 lower for the Genezis technology than for the Plant technology.

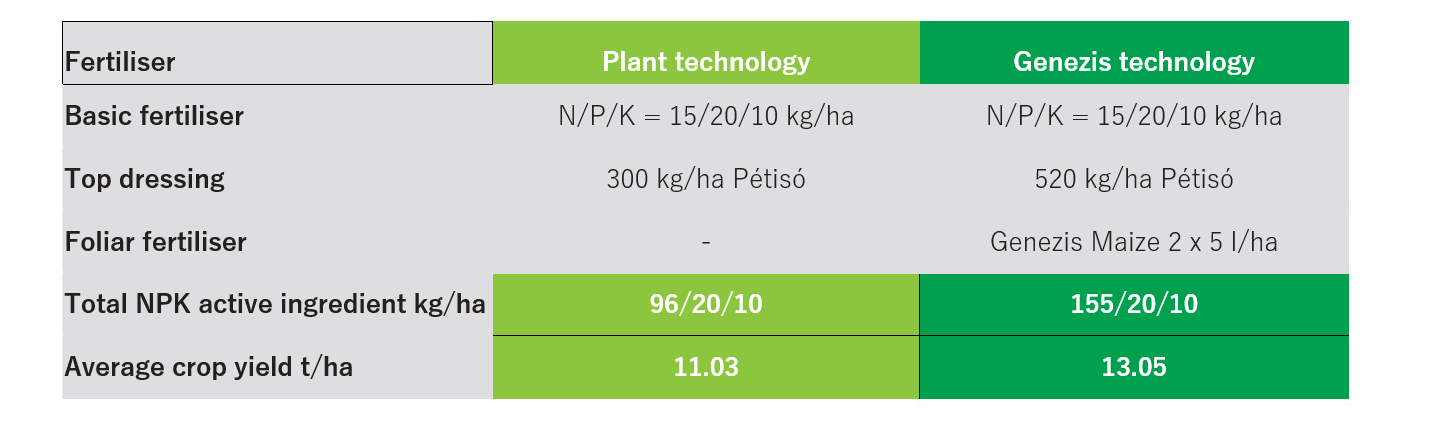

In another Genezis experiment (Tiszanagyfalu), the Plant field received 96/20/10 and the Genezis field received 155/20/10 of NPK active ingredients. The average crop yield of maize was 11.03 t/ha and 13.05 t/ha, respectively. Calculated at current prices, the production cost of the Plant field was HUF 340,000/ha, and HUF 396,000/ha for the Genezis field.

At a farmgate price of HUF 75,000/t, an additional sales revenue of HUF 151,500/ha, so HUF 95,500/ha additional income was realised with the Genezis technology. At a farmgate price of HUF 100,000/t, these were HUF 202,000/ha and HUF 146,000/ha respectively. This means that the application of a higher, but not unrealistically high additional amount of nitrogen results in a significant additional income even at current farmgate prices and production costs. There was no significant difference in the break-even point, and it was also quite low (HUF 30,825 and 30,344/tonne). Experience gained from our two experiments described above is that a harmonious dosage of fertilisers, adapted to crop needs and soil conditions, and based on expert counselling, can lead to higher average crop yields and higher incomes, as higher fertiliser prices are associated with higher crop prices.